In this essay about sacred sexuality in Mesoamerican traditions, readers journey into the vivid heart of ancient worlds, where sexuality transcends mere physicality, becoming a profound gateway to cosmic truths. Grounded in meticulous scholarship yet rendered in richly poetic language, this essay explores rituals, symbols, and divine archetypes, revealing how the sacred and erotic intertwined inseparably in Maya and Aztec life. More than historical exploration, this narrative invites modern readers into deeper conversations about desire, spirituality, and identity, offering timeless insights into sexuality’s power as both personal transformation and universal connection—an intimate dialogue between humanity and the infinite.

Embodied Symbolism

To step onto the warm limestone plateau of Chichén Itzá at dawn was to enter into a language made entirely of stone. It was there, beneath the vigilant Yucatán sun, where fields of sculpted phalli silently narrated stories of fertility rites, life force, and cosmic continuity. Each carefully carved stone, heavy and weathered, was placed as deliberately as words in sacred prayer, each one recounting centuries of devotion and collective longing. As the sunlight touched these solemn rows of stone phalli, the shadows they cast on the earth stirred, extending outward and blending with the shadows of passing pilgrims. It was as though the stones themselves were quietly breathing, whispering a reminder that sexuality here was never merely a human affair, but a conversation shared with the divine, etched into the very skin of the world.

Within nearby temples, decorated pottery gleamed softly in the muted half-light. The sensual curves of ceramics, etched with figures locked in acts of love and ritual ecstasy, spoke clearly but without shame or reticence. Fingers pressed deep into clay; mouths frozen in states of rapture; scenes of tenderness, yearning, and sometimes the stark, quiet violence of desire were all meticulously etched into vessels designed to hold maize, cacao, or even the blood of sacrifice. These artifacts did not merely illustrate acts of pleasure—they sanctified them. Their depictions were not hidden away but stood openly within communal spaces, inviting touch and contemplation, preserving in fired earth the fundamental truth that eroticism was inseparable from fertility, survival, and cosmic renewal.

Beyond pottery and sculpted stones lay deeper mysteries—caves opening like secret mouths beneath the jungled mountains and valleys. These caves were seen not merely as hollows in rock but as wombs of the earth itself, portals to realms beneath the tangible world. Yet, paradoxically, the women whose wombs these caves symbolized were often prohibited from entering them, their sacred nature too potent, too dangerously close to the essence of creation. Thus, it fell to men to descend into these earthly wombs, carrying torches flickering in the subterranean darkness, illuminating ancient images on moist cavern walls—images of snakes intertwined, vines blossoming into erotic flowers, deities caught mid-embrace. Each drip of mineral-rich water echoed softly, sounding almost like human breath—heavy, rhythmic, expectant.

In the lowlands of the Maya, the fertile earth itself told a similar story of sacred communion. There, phallic stone carvings often lay half-hidden in lush vegetation, ivy-covered monuments weathered by countless rainy seasons. Time wore gently on these sculptures, rounding their once-proud edges, softening their power, slowly returning them to the ground from which they first emerged. For the Maya, fertility was never purely biological; it was cosmic, a constant dialogue with the gods conducted through symbols tangible enough to touch, to honor, and even to mourn as they slowly decayed.

This constant, gentle tension—between tangible presence and gradual dissolution, fertility and decay, creation and inevitable destruction—was embedded into every stone, every artifact, every ritual space. Even in their silence, the carved symbols of sexuality insisted upon their duality, their inseparable alliance of beauty and danger. And those who passed through these places, aware or not, became part of this same conversation, their lives momentarily interwoven into a story far older and far larger than themselves, a narrative deeply rooted in the earth’s body, where sexuality was celebrated openly as the deepest, most sacred engagement with the cosmic cycles.

And yet these physical forms were only one part of a much greater symbolic ecosystem, as intricate and alive as the verdant jungle that surrounded them. The spaces themselves—carved temples, secluded groves, ritual plazas—held within their precise geometry a layered map of cosmic relationships. Observing them closely, one noticed how architectural spaces mirrored celestial constellations and planetary alignments, the tangible symmetry echoing intangible harmonies in the heavens above. This was sexuality rendered sacred by its positioning, spatially and cosmically, each stone and carving a careful stroke of cosmic calligraphy.

Even more subtly, the cities themselves became profound symbols of erotic union, woven directly into their architecture. Streets formed like veins converging at the heart of temples, plazas circular like wombs at the city’s center, and stepped pyramids ascending towards the heavens, suggesting fertility itself rising from earthly origins toward divine communion. At Chichen Itza or Teotihuacan, the careful observer could trace pathways designed to mirror the ascent from earthly desires toward cosmic transcendence. Visitors, whether pilgrims or priests, moved through these streets with quiet reverence, their journey an enactment of sacred intimacy—the city itself becoming a lover who embraced, guided, and ultimately transformed.

Yet it would be insufficient to see these symbols as solely peaceful or harmonious. Embedded deeply within them was a darker pulse—a recognition of sexuality’s perilous power. Pottery shards discovered across ancient marketplaces depicted acts not merely joyous but also troubling: carnal excess that tilted toward ruin, desire pursued to the edge of self-destruction. This shadow aspect whispered that sacred sexuality was never purely safe or entirely contained; its inherent potency demanded careful ritual management, lest fertility tip into excess, creativity into chaos, life into death.

This darker nuance emerges vividly in one particular motif that recurs again and again—the enigmatic scorpion. Carved into pottery, etched into temple walls, and hidden within ritual texts, this creature symbolized both desire and danger, seduction and pain. A sting from this seemingly innocuous animal required healing rituals that themselves were profoundly sexual: piercing ceremonies, bloodletting rituals invoking ancestral pain and divine communion. The scorpion reminded the initiate that sexuality was never neutral—its sting always latent, capable of injecting both ecstatic communion and deadly transformation. The scorpion thus stood as a living paradox, simultaneously alluring and lethal, its very presence demanding respect, awareness, and careful balance.

In these tangible symbols—phalli, caves, ceramics, cities, and scorpions—Mesoamerican cultures encoded their most profound beliefs. Far from mere decoration or aesthetic curiosity, these symbols were active participants in an ongoing dialogue about human purpose and cosmic order. Sexuality was never isolated from life itself but intricately interwoven with all existence, a central thread binding the visible world to invisible realms. This constant interplay reminded practitioners that their own physical bodies, their desires, their deepest urges, were mirrors of cosmic truths, intimately connected to forces far beyond their individual lives.

Standing amid these ancient ruins today, one can still sense this silent, insistent teaching. Every carving and artifact whispers quietly but insistently that sexuality is not something separate from life, not isolated from spiritual longing or cosmic balance. Rather, it is woven into the earth itself, flowing through stone, soil, and blood, as inexorably present as breath. Through their art and architecture, these ancient civilizations left not only a record of their rituals and beliefs but also an invitation—an invitation to modern eyes to look deeper, listen closely, and understand intimately that here, beneath the sunlit stones and tangled roots, lies a vision of sexuality as sacred, profound, and eternally alive.

Immersion into Emotional and Erotic Depths

When pilgrims approached the jade-green altars, lush with offerings of flowers and fruits in bloom, their senses quickened, stirred by fragrances heavy with promise and the humid whispers of secret anticipation. Amid the fragrances of copal incense mingling with honeyed orchids and bruised cacao pods, they felt a stirring deeper than mere physical desire—a yearning that pulsed gently, relentlessly, beneath their skin. The ritual spaces, adorned with fresh blossoms still dripping with morning dew, seemed charged with the invisible presence of Xochiquetzal herself, the goddess whose breath was said to quicken the pulse and swell the fruit. Her touch was imagined like the first rains after a punishing drought: gentle yet overwhelming, subtle yet inescapably potent.

In Nahuatl, “xōchitl,” meaning flower, held a delicate ambiguity. It spoke of both blossoming fertility and unchecked excess—an emotional duality that quietly governed the rhythms of daily life. Flowers adorned bodies, hair, and temples, their scents rich and cloying, mingling with the humid air like whispered promises or quiet warnings. Floral perfume intoxicated the senses of worshippers as they prepared for ritual communion, weaving emotional tension with the sensual pleasure of anticipation. Each petal plucked and placed reverently on an altar held both the sweetness of erotic invitation and a lingering note of melancholy, acknowledging that the flower, at its fullest bloom, already carried the gentle inevitability of wilting, reminding participants of desire’s ephemeral nature.

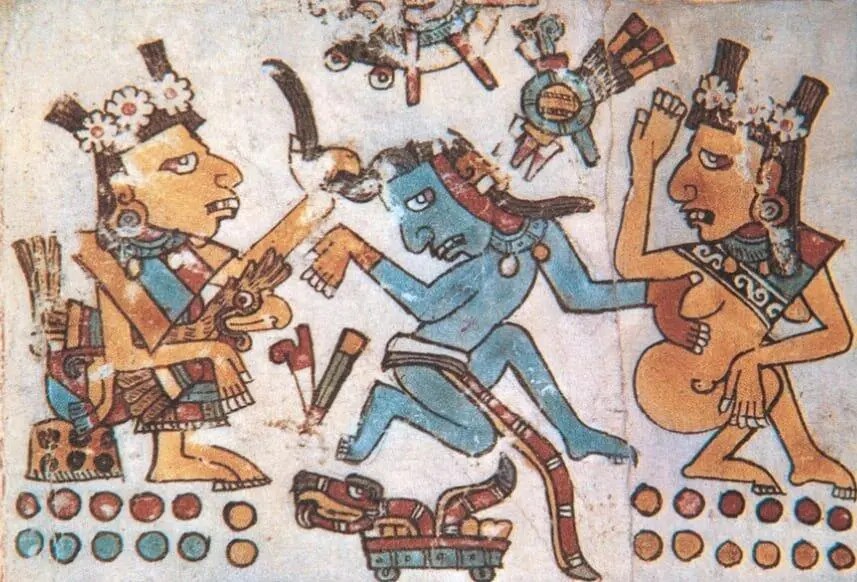

In temples shadowed by towering palms and dense jungle canopies, priests and priestesses enacted sacred rites whose emotional weight transcended simple pleasure. They did not merely perform sexuality—they embodied its emotional paradoxes, crafting rituals that blurred pain and pleasure, ecstasy and loss. In vivid ceremonies, temple dancers moved with slow, deliberate grace, their bodies painted with intricate symbols of fertility and longing. Their movements—fluid, unhurried, hypnotic—echoed deep, unspoken emotional tides: joy tempered by sadness, release tempered by longing, intimacy always balanced on the cusp of loss. Every gesture, from delicate caresses to moments of raw vulnerability, was choreographed to evoke deep emotion, immersing the viewer fully in the ritual’s erotic poignancy.

Among these rituals, one Maya practice particularly embodied emotional complexity: the bloodletting ceremony, a profound act involving piercing the genitals with stingray spines or obsidian needles. This act was neither punishment nor cruelty, but rather the deepest physical enactment of spiritual devotion. As blood dripped slowly onto bark paper, staining it with patterns reminiscent of blooming flowers, participants felt a profound mix of pain and exaltation, submission and empowerment. Their bodies trembled, not solely from pain, but from an overwhelming awareness that their sacrifice mirrored the cycles of the earth itself—blood given freely to nourish the cosmos, sustaining a harmony far greater than personal suffering.

Thus, sexuality in these sacred contexts was never merely physical—it was a potent emotional current woven deeply through the fabric of society. Emotional experiences connected the individual intimately to community and cosmos, creating a tapestry rich with longing, reverence, desire, and the bittersweet recognition of life’s transience. Participants emerged from these rituals not simply satiated or relieved but changed—carrying within them the emotional echoes of cosmic communion, an indelible feeling that lingered long after physical sensations had faded, a silent, emotional memory carried in the heart, ever rippling outward in quiet waves.

These emotional currents ran far deeper than mere physical sensation—they permeated the collective psyche, shaping identities, relationships, and the intricate social rituals surrounding sexuality itself. Consider the ceremonial presence of sacred intermediaries, known among the Aztecs as ahuianime, women and men whose very existence blurred the lines between sensuality, devotion, and communal healing. More than simply conduits of physical pleasure, these individuals moved quietly, gracefully between the realms of human longing and divine ecstasy. Their presence at rituals and festivals was not merely ornamental or symbolic—it was emotionally essential, their touch carrying both spiritual and sensual comfort, their whispered words of reassurance calming fears, dissolving barriers, and opening hearts to the transformative potential of ritual union.

Within the candlelit chambers of the temples, amid drifting clouds of incense heavy with copal, the emotional significance of these ritualized encounters was palpable. Visitors and priests alike approached these sacred intermediaries not with shame or fear, but with quiet reverence, recognizing that emotional communion required profound vulnerability. Moments of intimacy, often fleeting yet profoundly charged, left indelible emotional traces—traces felt long after rituals concluded, woven into dreams, memories, and quiet conversations whispered beneath moonlit skies.

Yet emotional complexity also manifested through quieter channels, subtly embedded in the everyday lives of the Maya and Nahua alike. Even simple exchanges of flowers carried deeply layered emotional meaning—each blossom chosen deliberately, communicating longing, caution, seduction, or spiritual reverence without the need for explicit words. The Nahuatl language itself was richly textured, offering intricate emotional nuances through metaphor and implication rather than overt declaration. Words like xōchitl, “flower,” conveyed subtle emotional undertones of desire and excess, simultaneously innocent and provocative. The careful selection of each flower thus became a language of unspoken emotional truths, hinting gently at inner states otherwise left undisclosed.

At times, however, emotional undercurrents erupted vividly into public life, dramatically revealing the paradoxes lying just beneath the surface. The tale of Xochiquetzal and her mortal lover, Yappan, resonated deeply precisely because it captured the emotional risks inherent in desire itself—the goddess’s embrace simultaneously an act of intimacy and devastation, seduction followed by transformation and loss. The emotional weight of such myths was not lost upon the faithful, for whom these stories resonated deeply in their own lived experience of love, loss, joy, and suffering. They knew well that the erotic held the power not just to create but also to utterly transform—or destroy.

Thus, sacred sexuality among the ancient Mesoamericans was an emotionally intricate dance, pulsing subtly yet insistently beneath surface actions. These cultures recognized something profoundly true about desire: its ability to elevate or humble, to bring ecstatic union or profound solitude, to heal or deeply wound. They understood intuitively that to enter sexuality’s sacred waters meant accepting emotional vulnerability as essential, recognizing intimacy as a delicate balance between surrender and control, joy and sorrow, life and death.

In this fluid, emotional space lay perhaps the deepest truth of their sacred sexuality—the recognition that desire itself is profoundly ambivalent, neither wholly safe nor fully dangerous. It simply is—fluid, shifting, endlessly renewing itself like rivers carving paths through rock, like tides washing away and reshaping shores. In accepting this ambivalence without judgment or fear, the Maya and their Mesoamerican kin embraced sexuality as a sacred emotional journey, a profound meditation upon existence itself, forever unfolding, forever rippling quietly beneath the surfaces of their lives.

Ritual as Active Transformation

At twilight, the temples came alive with fire. Flames danced on stone altars, sputtering fiercely as copal incense crackled in the heat, sending fragrant smoke spiraling upward, carrying whispered prayers toward unseen gods. Shadows moved restlessly along temple walls, bodies illuminated briefly by the flickering orange glow—priestly hands steady and solemn, eyes glazed by trance or anticipation, each gesture heavy with meaning. Here, in the fiery heart of sacred ritual, participants stood at the brink of transformation, their skin tingling with the intensity of the moment, aware that the smallest hesitation could unravel everything, yet could also ignite revelations powerful enough to reshape their understanding of existence itself.

Ritual was fire made flesh, a living enactment of the elemental tensions that underpinned the Mesoamerican universe. The Maya understood well the fierce yet paradoxical nature of this sacred fire. In bloodletting rituals, participants willingly pierced flesh, offering streams of bright crimson to smoldering braziers, the smoke twisting and thickening as blood met flame. They knew pain intimately as a sacred bridge, connecting human suffering with divine communion. The slow burning of copal resin mingled with blood’s acrid tang, forming a potent alchemical mixture that blurred boundaries between agony and ecstasy. Amidst such rituals, the distinction between sacrifice and celebration collapsed entirely, for pain here was never merely destructive—it was generative, a fiery catalyst propelling mortals toward profound communion with the divine.

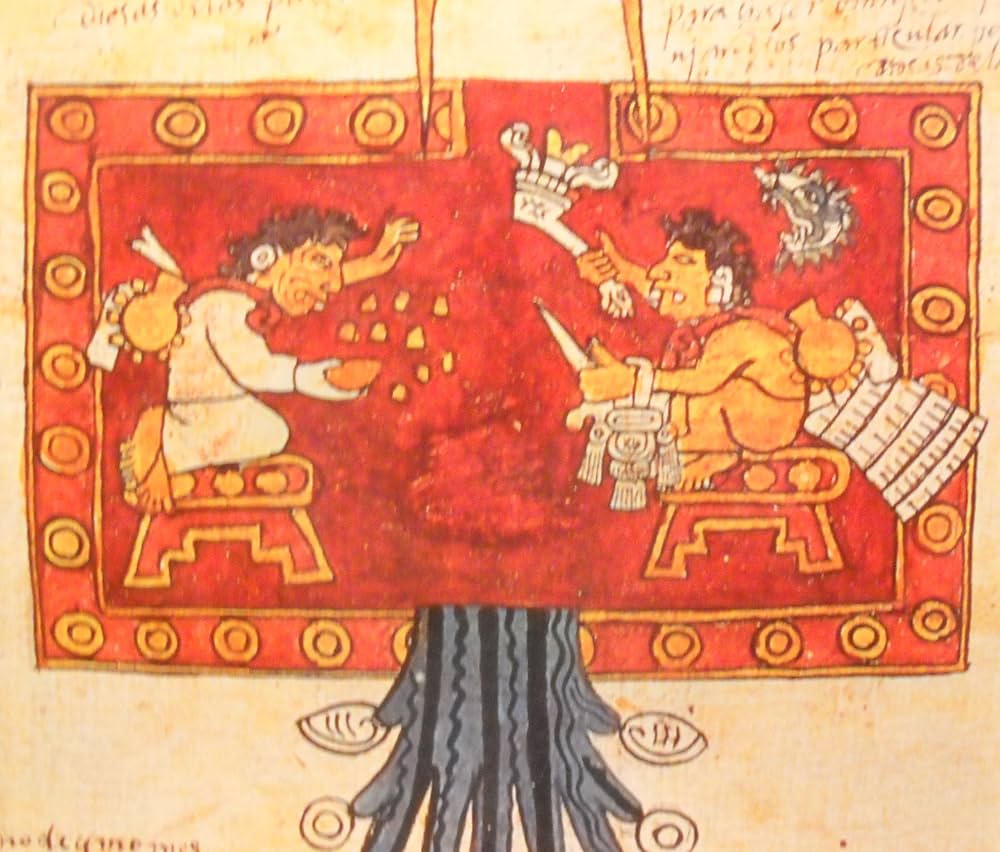

For the Aztecs, too, fire symbolized urgent, transformative power. Ceremonies dedicated to Xochipilli, the radiant “Prince of Flowers,” pulsed with fierce energy. Drums pounded relentlessly beneath painted ceilings, bodies moving rhythmically in escalating circles around central flames, each step amplifying tension. Participants danced not merely to express joy or devotion, but to invoke the god’s passionate force—an ecstatic rhythm pushing them beyond physical exhaustion into ecstatic trance. As bodies heated, boundaries blurred; dancers felt themselves become vessels of divine passion, embodiments of the very flame that illuminated them, their humanity momentarily consumed by ritual fire, then returned, tempered and renewed.

Yet the flame also bore profound paradoxes. Among the Nahuas, the goddess Tlazolteotl presided over carnal transgressions—her sacred rites involved acts which, to outside eyes, might seem morally ambiguous or socially dangerous. Her fire purified not by burning away sin, but by engulfing it fully, transforming shame into absolution. In her rituals, participants openly confronted their deepest urges, acknowledging forbidden desires, embracing their contradictions, ultimately releasing shame in cleansing conflagration. Each confession whispered to Tlazolteotl was itself a flame—dangerous yet purifying, destructive yet liberating. In surrendering to the goddess, worshippers burned away spiritual impurities, emerging reborn from rituals that pushed emotional and ethical boundaries to the breaking point.

This paradox—the simultaneity of destruction and creation, danger and renewal—animated every act. The priests and priestesses tending sacred fires understood their dual role as both guardians and gatekeepers. They stoked flames carefully, never allowing them to smother or extinguish, yet also never letting them escape control. Ritual fires, though intense, were meticulously structured, reflecting the careful tension at the heart of Mesoamerican spiritual consciousness: order balanced precariously on the edge of chaos, ecstasy poised eternally against restraint. Each act within the temple fire was thus an enactment of cosmic equilibrium, a demonstration of the fragile yet exhilarating balance between human passion and divine will.

This controlled intensity found its most vivid expression in rituals involving sacred sexuality, acts performed not merely for physical union but as living metaphors of cosmic renewal. In secluded temple chambers, illuminated softly by torchlight that cast long, trembling shadows, couples united ceremonially beneath the watchful eyes of priests. Their union, deliberate and unhurried, mirrored celestial alignments—the rising and setting of Venus, the waxing and waning of the moon—each rhythmic movement corresponding precisely to cosmic cycles that governed life itself. In these rites, passion was carefully cultivated, sustained at a peak of intensity without haste, participants becoming embodiments of the cosmos at play, human passion transformed into divine drama.

Yet the flame’s intensity sometimes demanded more: at times, the symbolic and metaphorical was not enough. In rituals of greater urgency, physical intimacy was heightened by simultaneous acts of pain—small incisions made deliberately along skin, leaving delicate crimson lines that wept slowly in the firelight. This blending of pleasure and pain served as a visceral reminder that creation and destruction were inseparable. Participants who experienced these rituals described an overwhelming clarity emerging amid the flames, an intuitive grasp of life’s paradoxical nature—the pain itself not punishment but a profound path to clarity, a revelation borne from the depths of human vulnerability.

Priests themselves were not merely facilitators, but active participants, their bodies becoming vessels of sacred transformation. Covered in intricate symbols painted in vibrant colors derived from flowers and minerals, they moved among celebrants, guiding rituals through whispered chants and careful gestures. Their presence lent structure to the fiery chaos, ensuring intensity remained purposeful, transformative, never drifting into mere spectacle. The priests’ words, rhythmic and repetitive, ignited emotional responses that pulsed through participants, intensifying the flames within each individual heart until the distinctions between mortal and divine, human and elemental, dissolved entirely.

Among the Maya, this tension between ecstasy and control reached perhaps its highest expression in rituals involving visionary substances—psilocybin mushrooms and cacao preparations laced with potent spices. Here, the transformative fire entered participants internally, igniting visions that erupted vividly from the depths of their consciousness. Under these substances’ influence, celebrants traveled inward to confront hidden fears and desires, the flames illuminating their darkest recesses, stripping away illusions, leaving only truth behind. Participants reported visions not merely symbolic but profoundly instructive—direct encounters with ancestors, spirits, and gods, whose fiery presence imparted knowledge and demanded accountability. The ritual thus transformed not only their perception but their entire being, leaving participants irrevocably altered, as if the flames had reshaped their very souls.

At ritual’s close, as temple flames burned lower, their fervor softening to quiet embers, participants emerged transformed—aware that something profound had shifted within them, although perhaps uncertain precisely what. They walked slowly back into their ordinary lives, carrying the flame’s lingering heat beneath their skin, its revelations continuing to smolder softly within their hearts and minds. Each ritual thus ended in gentle ambiguity: flames reduced to ash, yet paradoxically more potent in memory than in the moment itself.

In this careful yet passionate dance, Mesoamerican sacred sexuality became the embodiment of fire’s transformative promise. Desire ignited became wisdom, passion became revelation, suffering became clarity. Through carefully controlled intensity, participants learned that to truly know the divine was not merely to observe or worship from afar—but to burn intimately with it, feeling firsthand the inexorable heat of existence itself.

Intellectual and Divine Inquiry

Yet beneath the visceral intensity of ritual and emotional immersion lay a subtler realm—an intellectual landscape where priests and philosophers alike pondered endlessly over the intricate relationships between human desire, sacred practice, and cosmic order. Here, beneath temple archways carved with intricate glyphs shimmering gently in torchlight, men and women spoke quietly, questioning, reflecting, forever unraveling mysteries through dialogues that looped endlessly inward upon themselves. In these whispered conversations and patient silences, sexuality was not merely enacted but scrutinized, understood not just physically or emotionally, but philosophically—probing deeper truths hidden beneath the surface of ritual and myth.

Priests would gather in contemplative circles beneath canopies woven with feathers, their voices murmuring questions into the fragrant air, thick with the scent of crushed orchids and smoldering copal. “What is desire,” they asked quietly, “if not the yearning of the cosmos made flesh? What is union if not the fleeting reconciliation of dualities—the meeting of sky and earth, mortal and divine, life and death?” These were not rhetorical musings, but genuine inquiries, opening paths to endless interpretative layers. Every conversation became a recursive spiral—questions spawning deeper questions, answers inevitably becoming new riddles, each resolution birthing fresh mysteries. In the silence that followed each response lay an invitation, a beckoning to push further, deeper, never settling into static certainty but always plunging forward into uncertainty, driven by curiosity alone.

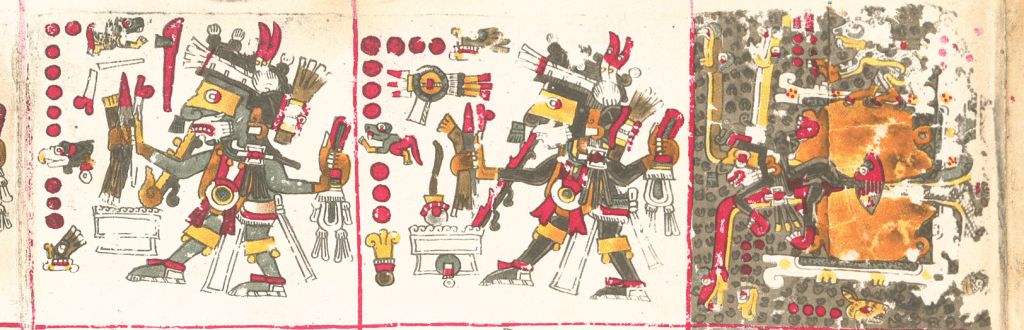

Texts and codices scattered across stone benches and sacred libraries spoke similarly, inscribed meticulously in obsidian-black ink on supple fig-bark paper. Illuminated by torch flames, priests read slowly, tracing lines with fingers inked with sacred pigment, decoding images and symbols whose complexity defied simple interpretation. Glyphs depicting erotic encounters were studied not merely for their literal meanings but as symbolic riddles demanding relentless intellectual engagement. Within these codices, gods and mortals danced together, intertwined in embraces both ecstatic and sorrowful, embodying cosmic paradoxes. Their acts were never straightforward; each gesture carried embedded questions that defied easy answers—what did it mean when Xochipilli, prince of pleasure, was simultaneously portrayed with symbols of sacrifice and pain? How could the erotic goddess Tlazolteotl embody both transgression and purification?

Such complexities demanded careful analysis. Scholars argued gently but persistently, their discussions spiraling outward into ever more abstract reflections on duality and paradox. They sought clarity in paradoxes rather than simple resolutions, employing careful logic and methodical questioning. The act of sacred sexuality itself became an intellectual puzzle, a philosophical koan whose resolution lay not in neat answers but in the tension between contradictions. Here, intellectual rigor did not dispel mystery; it deepened it. Sexual acts were analyzed not to tame or simplify, but precisely to reveal their inherent ambiguities, contradictions, and multivalent truths.

Yet even in their abstract questioning, scholars and priests never lost sight of the concrete, bodily truth of sexuality itself. Their intellectual dialogues always returned gently, inexorably to sensory and physical experience—drawing again and again on concrete imagery of petals unfurling, blood dripping, bodies trembling in ritual embrace. These sensory anchors kept discussions tethered to reality, ensuring intellectual exploration remained grounded rather than drifting into abstraction. Philosophers recognized intuitively that true insight required balance—abstraction tempered by physicality, conceptual exploration grounded always in tangible experience.

Thus, beneath temple ceilings painted with constellations and sacred symbols, intellectual inquiry became a subtle but essential ritual itself. Here, sexuality was not simply experienced but profoundly understood, each dialogue another step deeper into cosmic truth—an endless spiral of intellectual expansion, forever circling closer to the mystery at the heart of existence itself.

Such intellectual explorations found their deepest resonance in the stories whispered among initiates, narratives carefully preserved not merely as myths but as vessels of profound philosophical inquiry. One such narrative recounted how Tezcatlipoca, the “Smoking Mirror,” god of contradictions and illusions, once disguised himself to seduce a mortal king. This tale was repeated with quiet reverence beneath the murmuring palms, in courtyards flickering with firelight and incense smoke. As listeners leaned forward, eager yet uncertain, storytellers raised subtle questions that lingered in the twilight air: Was desire real or illusory? Could mortal hearts discern truth from divine deception, intimacy from illusion? Within these seemingly simple tales lay profound insights into the nature of human longing, identity, and the precarious boundary between reality and perception.

Such stories were recounted slowly, deliberately, never rushing toward simplistic conclusions. Each retelling brought fresh nuances to light, prompting listeners to ask new questions: What does it mean to surrender one’s self to desire fully, knowing that desire is itself inherently transient, its satisfaction ephemeral? What truths emerge when identity itself dissolves in passion’s fire? The Aztec listeners recognized in Tezcatlipoca’s paradoxical nature a reflection of their own internal contradictions, their own buried impulses. They understood intuitively that sacred sexuality was a mirror held up to humanity itself, its surface shimmering not merely with reflections of divine beauty but also shadowed truths—complex, unsettling, yet deeply liberating.

At the heart of such intellectual inquiries lay a profound respect for ambiguity, paradox, and unresolved tension. The Nahua believed strongly in the concept of nepantla—a state of liminality, perpetual transition, an intellectual space where boundaries blurred and certainties dissolved. Priests and scholars deliberately cultivated this state, using sexuality as a profound metaphor for life’s inherent instability. Ritual and myth thus became intellectual tools, fostering inquiry that embraced contradiction rather than seeking simplistic resolution. They understood that true wisdom did not simplify complexity—it embraced it, welcoming uncertainty as essential, necessary, and ultimately generative.

Such sophisticated understanding was captured visually in temple art itself—murals depicting gods and humans entangled in acts simultaneously erotic and enigmatic. Figures twisted in passionate embraces, yet their expressions hinted subtly at deeper uncertainty, hesitation, even loss. These murals were studied carefully by initiates who recognized the implicit intellectual invitation: to question relentlessly, interpret thoughtfully, never settling for surface meanings but always peeling back layers of ambiguity. Each painting thus became a silent partner in ongoing inquiry, reminding observers that the quest for understanding sexuality—and by extension, existence itself—was never-ending.

Yet this relentless questioning never descended into mere abstraction. Mesoamerican philosophers remained tethered firmly to the sensual, tactile realities of life itself. They knew well that intellectual insight devoid of embodied experience was sterile, empty, lifeless. Thus, even their most abstract discussions concluded with rituals returning them to sensory grounding—flowers crushed between fingers, incense inhaled deeply, bodies feeling once more the soft caress of ritual garments or the sharp sting of ceremonial blades. Intellectually, they reached upward and outward, but always returned to earth, reaffirming life’s immediacy and vitality as essential counterpoints to philosophical exploration.

Thus, beneath the quiet skies streaked crimson at twilight, the intellectual and divine realms intertwined profoundly, each feeding endlessly into the other. Questions begat more questions, spiraling gently upward toward cosmic insight, yet forever rooted in the fertile soil of lived experience. And within this careful balance—between intellect and embodiment, certainty and ambiguity—lay perhaps the deepest truth of all: that sexuality itself was the ultimate riddle, never fully solved, yet infinitely rewarding in the endless pursuit of understanding.

Expansive Synthesis and Return

In the wake of ritual, silence reclaimed its dominion, settling like mist over temple courtyards and sacred plazas now deserted beneath constellations slowly wheeling overhead. Participants emerged from their experiences quietly changed, carrying with them intangible revelations, understandings that hovered on the periphery of language. It was not merely emotional release, nor intellectual epiphany, but something subtler and far more expansive—a spiritual insight, felt deeply but articulated only with great difficulty. They walked beneath stars whose quiet radiance seemed suddenly alive with unspoken meanings, each celestial point mirroring something newly awakened within them. The heavens above were not distant or indifferent; they shimmered gently with silent promises, each star a fragment of cosmic understanding, intimately linked to the profound transformations of the human heart.

Those who experienced sacred sexuality emerged bearing a widened awareness, a vision extending beyond personal boundaries into the spaciousness of universal truths. It was as though their souls, briefly untethered by ritual ecstasy, had traveled through unseen pathways connecting them not only to ancestors and deities but to the cosmos itself. They returned with spirits subtly expanded, capable of perceiving connections previously hidden beneath layers of daily life and ordinary perception. Their understanding was not merely theoretical but profoundly embodied, felt in the marrow and breath—a spiritual knowledge that illuminated ordinary existence with transcendent meaning, revealing life’s every gesture as part of an infinite cosmic dance.

This expansive awareness was captured vividly in the symbols carved carefully upon temple walls: spirals endlessly unfurling, circles intersecting, serpents devouring their tails. Each figure represented infinity, wholeness, unity—the seamless integration of opposites, the inseparable union of sacred and mundane, self and cosmos, desire and divine purpose. To walk these halls after ritual was to move through a tangible reminder of life’s intrinsic interconnectedness, every step an affirmation of the infinite embedded within the finite. Here, spirituality was never distant or abstract; it infused stone and flesh alike, whispering insistently through symbols etched deeply into temple walls, murmuring gently through the rhythm of breathing bodies.

Yet, even as the participants sensed this infinite expansiveness, they also felt a profound humility—a gentle recognition of their place within a far larger tapestry. Ritual did not inflate the ego, but rather diminished it gracefully, allowing a sense of spaciousness to bloom quietly within the soul. To glimpse cosmic truths was to recognize simultaneously one’s own smallness and one’s profound interconnectedness, each insight bringing gentle dissolution of boundaries. The sacred sexuality rites thus functioned as powerful spiritual dissolvents, gently eroding egoic barriers, leaving only open space—an emptiness radiant with potential, a fertile void where profound spiritual insight could take root.

In these moments of spacious awareness, participants recognized sexuality as neither purely physical nor solely spiritual, but rather as the essential link joining body and cosmos, flesh and star, momentary pleasure and eternal truth. Their spirits opened like petals beneath moonlight, receptive, vulnerable, profoundly awake. They sensed themselves simultaneously finite and infinite—individual lives becoming droplets within a cosmic ocean, their desires mirrors reflecting universal longing. They felt deeply their profound, paradoxical existence: mortal yet eternal, separate yet inseparable from the endless rhythm of life and death, creation and dissolution.

Thus, beneath the gentle radiance of moonlit skies, ritual participants moved slowly outward into their everyday lives, forever altered, subtly yet irrevocably transformed. They carried within themselves a newfound spiritual spaciousness, a quiet awareness of life’s boundless complexity and profound simplicity. To experience sacred sexuality was not merely to touch another or know oneself intimately—it was to glimpse the universe within every heartbeat, feeling the cosmos pulse gently beneath one’s skin.

Such expansive insights lingered quietly within the participants long after rituals concluded, shaping their everyday existence in subtle yet unmistakable ways. Ordinary gestures—hands reaching to pluck maize, fingers weaving cloth, lips murmuring prayers—were now infused with deeper resonance, each movement imbued with sacred significance, each breath charged gently with cosmic meaning. Life itself became an ongoing meditation, each day an opportunity to embody the profound understanding glimpsed within ritual spaces. The world remained the same—fields blooming beneath radiant sun, rain drumming softly upon temple rooftops, children laughing—but participants perceived it differently, noticing hidden layers previously overlooked, subtle connections that bound their small lives to greater cosmic rhythms.

In villages scattered among mountains and jungles, stories quietly spread of ritual participants whose gaze had softened, eyes shimmering with newfound serenity, voices gentled by an awareness that defied words. Elders nodded knowingly, recognizing the quiet transformation—the soul returned spacious, bearing within it fragments of eternity. Conversations beneath market canopies or beside flowing rivers carried subtle, implicit acknowledgment of shared truths: that sexuality was not merely human, but profoundly sacred, a reflection of cosmic harmony revealed through simple acts of intimacy, vulnerability, and love. These were conversations without urgency, words drifting like smoke, unhurried yet filled with profound wisdom, a gentle dialogue bridging earthly life and cosmic understanding.

And within the temples themselves, priests carefully recorded these subtle revelations in codices richly adorned with symbolic imagery—spirals, serpents, flowering vines endlessly intertwining. Their glyphs captured profound truths that language could only gesture toward, hinting gently at life’s intrinsic interconnectedness, sexuality’s profound spiritual dimension, and humanity’s place within the cosmic tapestry. Each codex thus became a vessel, quietly holding space for future generations, whispering subtly of insights gained through sacred rites, reminding initiates that every physical encounter contained infinite spiritual potential, every ordinary moment a sacred possibility awaiting realization.

Those who experienced these rites firsthand understood deeply the gentle paradox at their core—that true spiritual expansiveness required intimacy, profound cosmic understanding demanded vulnerability, and infinite connection emerged precisely through mortal fragility. The very openness that allowed cosmic insights to flow was rooted deeply in bodily surrender, the acceptance of human limitation, and the courage to embrace both joy and sorrow. Sacred sexuality, in the end, became not merely an act but a spiritual practice—an ongoing, gentle surrender to life itself, each embrace a quiet acknowledgment of the sacredness permeating every breath, every touch, every heartbeat.

So participants returned, not as isolated individuals but as gentle ambassadors, carrying quietly within their souls the spacious wisdom discovered beneath temple roofs and starry skies. Their daily lives now became subtle teachings, silent invitations for others to perceive sexuality as sacred, intimacy as profound spiritual communion, and ordinary existence as infinitely meaningful. They moved gracefully, quietly among their people, eyes soft with quiet knowledge, hearts open with gentle humility, spirits expansive yet deeply grounded in earth. Through their subtle transformations, the entire community was gently elevated, the cosmic truths glimpsed within ritual gradually permeating society itself, weaving quietly into daily rhythms, rituals, and relationships.

Thus, in gentle silence beneath moonlit skies, Mesoamerican traditions quietly affirmed that sacred sexuality was ultimately a pathway—a journey not merely toward pleasure or intimacy, but toward profound spiritual expansiveness and cosmic unity. Participants discovered not just new aspects of themselves, but infinite possibilities within life itself, realizing in quiet moments of clarity that every act, every touch, every whispered word contained the universe’s gentle heartbeat. And in that quiet realization—beneath stars shimmering softly in infinite space—lay the greatest truth of all: that sexuality itself, when approached as sacred, gently reveals humanity’s intimate, inseparable connection with the cosmos, the quiet, eternal mystery forever pulsing within every living being.

Epilogue

To understand sacred sexuality as practiced in ancient Mesoamerican traditions is to grasp something deeply essential—something not only historical or cultural, but profoundly universal. At a time when contemporary society grapples openly and urgently with questions surrounding gender, sexuality, identity, and the intricate dance between masculinity and femininity, these ancient cultures offer nuanced wisdom, subtly instructive and timelessly relevant.

In the careful balance of creation and destruction, vulnerability and strength, these traditions reveal sexuality as an inherently complex dialogue, one deeply respectful of difference and paradox. Ancient priests understood intuitively what modern cultures often struggle to articulate—that sexuality is neither simple nor purely physical, but an expansive spiritual practice grounded in profound respect for the body’s inherent truths and mysteries. Their rituals offered powerful metaphors for embracing complexity, teaching us to approach difference and duality not as threats to identity, but as invitations toward richer understanding and deeper communion.

Moreover, these ancient narratives reveal that sexuality and gender have always existed along fluid spectrums rather than rigid binaries. Deities embodying simultaneous aspects of beauty and danger, pleasure and pain, masculine and feminine, teach contemporary minds something critical: that identity itself is a sacred mystery, continuously unfolding. Mesoamerican spiritual practices affirmed that within each individual resides infinite potentiality, a vibrant plurality of selves, desires, and expressions. To recognize and honor this multiplicity today is to reclaim profound cultural wisdom—wisdom capable of softening contemporary divisions, fostering compassionate dialogue, and inviting authentic intimacy among diverse communities.

Thus, the value of revisiting Mesoamerican sacred sexuality today lies precisely in its gentle insistence upon nuance, fluidity, and interconnectedness. These traditions quietly challenge modern anxieties about identity, gender, and sexuality, offering instead gentle yet potent affirmation—that diversity in identity and desire enriches, rather than threatens, human experience. They remind contemporary cultures that sexuality’s true power resides not in rigid definitions or imposed categories, but in open-hearted exploration, genuine vulnerability, and respectful communion—qualities essential not only to intimacy, but to human society itself.

In revisiting these ancient teachings, modern readers are gently reminded of a vital truth: that to honor sexuality as sacred is ultimately to honor humanity itself, in all its beautiful complexity and infinite potential.