Every now and then one stumbles upon an extra tidbit of information that brings an ancestral family story into clearer focus and sheds light on their existence which is so far removed from our own in many ways. We get a hint of what they were going through and that can make us feel more in touch with them and their lived experience.

THE NOTE

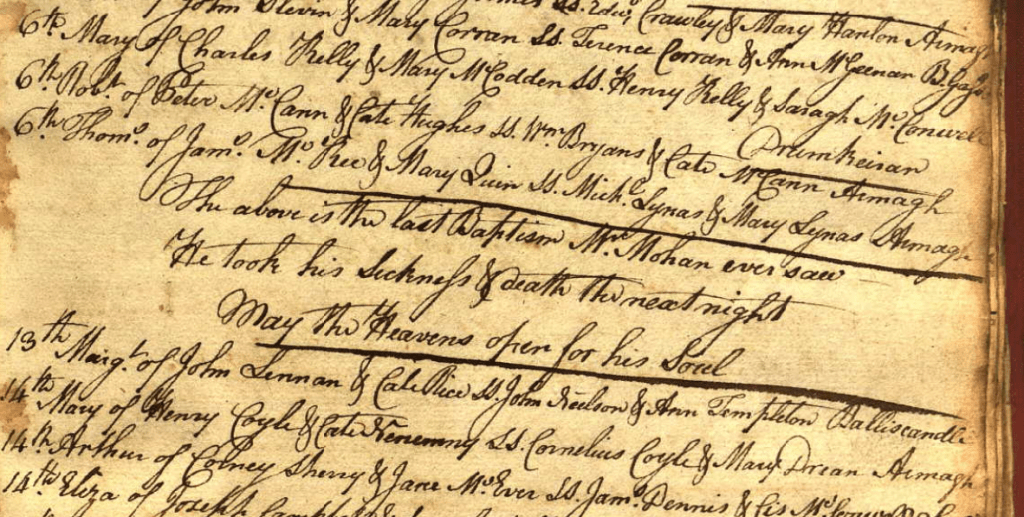

While researching our third great grandfather, James McCann (born 1792 • Armagh, Northern Ireland, died 11 Nov 1864 at Ballybohill, County Dublin, Ireland) I discovered he had a sister, Saragh born in March of 1799 in Armagh. At the top of the page there is a disheartening inscription: “January 1799 This year to us will not be kind“. Foreboding to say the least. Thumbing through the other pages I did not see any other notations like this other than again in March of the same year (below). The handwriting appears the same on the pages fore and aft so there must have been good reason for the scribe to make these notes at that time. Upon further research the prophecy was quite right.

The economic situation in Ireland was difficult in 1799. The country was experiencing a famine, and many people were struggling to make ends meet. The inscription “1799 This year to us will not be kind” may have been a reflection of the fear and anxiety that many people felt at the time. In 1799:

- The United Irishmen Rebellion had taken place in May of 1798. The rebellion was largely unsuccessful, but it led to a number of repressive measures being taken by the British government.

- Theobald Wolfe Tone, a leader of the United Irishmen, is executed in November.

- The British government suspends habeas corpus, which means that people can be arrested without being charged with a crime.

- The British government arrests suspected rebels, including many members of the United Irishmen.

- The British government transports many Irishmen to Australia as punishment for their involvement in the rebellion.

These are just a few of the many events that took place in Ireland in 1799. It was a year of great political and economic turmoil. The scribe saw the handwriting on the wall, as it were, and hand-wrote the message in the Parish Book. The political and religious situation in Armagh was also difficult in 1799. The city was experiencing a period of sectarian violence, and there was a great deal of fear and anxiety among the population. And with good reason.

The Armagh Riots of 1796-1797 were a series of sectarian disturbances that took place in Armagh. The riots were the culmination of years of tension between the Protestant and Catholic communities and they resulted in the deaths of dozens of people and the destruction of property. The British government responded to the riots by sending troops to Armagh, and by imposing martial law. However, the violence continued, and it was not until the end of the year that the riots finally subsided.

The same scribe made another prediction with the inscription “What was said will come at last.” This is harder to understand what this is referencing directly. The statement may have been a reflection of the belief that the violence would eventually end, and that peace would eventually be restored. But it seems to be referring to something that was said, likely by a leader of one of the factions involved in the tensions. From the events later in the year it would seem the scribe wasn’t quite on point.

For Catholics like the McCanns things got worse. The year 1800 was a year of transition for Armagh. The Armagh Riots had ended in 1797, but the tensions between the Protestant and Catholic communities remained. The Act of Union, which united Great Britain and Ireland, was passed in 1800, and this had a significant impact on Armagh.

The Act of Union led to a number of changes in Armagh. The county lost its status as a separate entity and became part of the new United Kingdom. The Orange Order, which had been formed in 1795, became increasingly powerful in Armagh. The Order played a role in the suppression of the Catholic population and in the promotion of Protestant supremacy. By the late 1820s James McCann moved his family to Feumore in the Glenavy Parish of Antrim.

Further along in the Armagh Parish Book, in the month of June 1799, there is a note on June 6th: “The above is the last Baptism Mr. McMahon ever saw. he took his sickneys and death the next night (June 7th). May the heavens open for his soul.” It is interesting that he is called “Mr.” Why is that?

In the Catholic Church, the title “Mr.” is used to address seminarians and other students for the priesthood. It was once the proper title for all secular clergy, including parish priests, the use of the title “Father” being reserved to religious clergy (“regulars”) only. The use of the title “Father” for parish clergy became customary around the 1820s. So, it is possible that Mr. McMahon was a seminarian or other student for the priesthood who died before being ordained. It is also possible that he was a parish priest who was not yet given the title of “Father.”

While not directly related to the McCann family, these notations provide insight into their lives in Armagh at the turn of the century. Moral of the story: Look beyond the bits about your family and peruse the whole page and the pages before and after – there are sometimes further clues that may help flesh out your family story and make it a richer experience for both the reader and researcher.

P.S. If anyone has more information about the McCann family in Armagh, and or in Antrim, please leave a comment and include any links you may have as well. Thank you in advance. Sláinte

I value your thoughts and opinions; please share them here.