SUMMARY: This article delves into the nuanced experiences of people living in 18th-century Germany’s borderlands, specifically in Hesse and Bavaria. It examines how fluctuating borders impacted daily life, governance, and cultural identity, weaving together personal stories and historical context. The article highlights the relevance of these borderlands in shaping ancestry, showing how modern genealogy can unravel complex family histories shaped by these fluid boundaries. It’s a reflective exploration of identity, migration, and the human experience across time.

In the heart of 18th century Germany, where the borders of Hesse, Bavaria, and Thuringia converged, a unique cultural, economic, and political life unfolded. This region, encompassing areas such as Fulda, Eiterfeld, and Bad Kissingen, served as a microcosm of the complex dynamics that characterized life in the borderlands of the Holy Roman Empire. The experiences of these “border people” offer invaluable insights into the nature of identity, community, and statecraft in a world where borders were as much about negotiation and opportunity as they were about division and control.

While this topic might seem rather scholarly at first glance, viewing it through the lens of genealogy and family history research allows us to connect more deeply with our ancestors’ lives. The land they lived on and the natural world around them provide us with important clues about their daily experiences. Add to this the historical events and circumstances of their time, and we begin to paint a vivid picture of their world. This article aims to bring into focus how living on or near constantly changing borders shaped the lives of our forebears, offering us a unique window into their challenges and opportunities.

The concept of borders in 18th century Germany differed significantly from our modern understanding. As scholars Conrad and Křížová note, “The early modern period finally saw efforts to unify state, tax and customs borders.” However, these efforts were far from complete, and the lived experiences of those in the borderlands reflected a reality where political boundaries were often porous and fluid.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who traveled extensively through this region, captured the essence of borderland life in his writings. In a letter dated 1780, he observed, “Here, where three principalities meet, one finds a curious mixture of customs and dialects. The people seem to embody the very essence of what it means to be ‘in-between’.”

“When you’re out of Schlitz, you’re out of beer”

This ‘in-between’ status was not merely a cultural curiosity but had profound economic implications. Local merchants and traders often exploited the differences in taxation and regulation between territories. As one contemporary account from a Fulda merchant’s diary reveals, “On Tuesdays, we bring our wares to the Bavarian side, where the duties are lower. By Thursday, we’re back in Hesse, selling what we couldn’t in Bavaria. It’s a delicate dance, but one that puts bread on our tables.”

This historical account of cross-border commerce in 18th-century Germany parallels modern practices in the Portland, Oregon, and Vancouver, Washington area. Today, residents engage in a similar “delicate dance” of tax arbitrage. Vancouver residents, benefiting from Washington’s lack of state income tax, often shop in Portland to take advantage of Oregon’s absence of sales tax. Conversely, many Oregonians work in Washington to maximize income, while making large purchases in Oregon to avoid sales tax. This contemporary parallel demonstrates the enduring nature of borderland economic strategies, where individuals and businesses navigate differing tax regimes to their financial advantage, much like their 18th-century counterparts.

Of further note, Buffalo and Rochester, New York, where these ancestors settled, bore striking similarities to their German homeland. These cities sit on major waterways, serve as hubs of agriculture and commerce, and are close to the Canadian border, with Niagara Falls just an hour and a half to the west. The consistency in geographical and economic characteristics of their chosen homes, and our own today, spanning three centuries and thousands of miles, is remarkable.

The political fragmentation of this central German region in the 18th century also created unique challenges and opportunities. The Prince-Bishopric of Fulda, for instance, found itself in a constant balancing act between its more powerful neighbors. A report from the Fulda chancellery in 1756 laments, “Our position is precarious. We must maintain cordial relations with Hesse-Kassel to the north, placate Bavaria to the south, and still assert our independence. It is a task that requires the wisdom of Solomon and the patience of Job.”

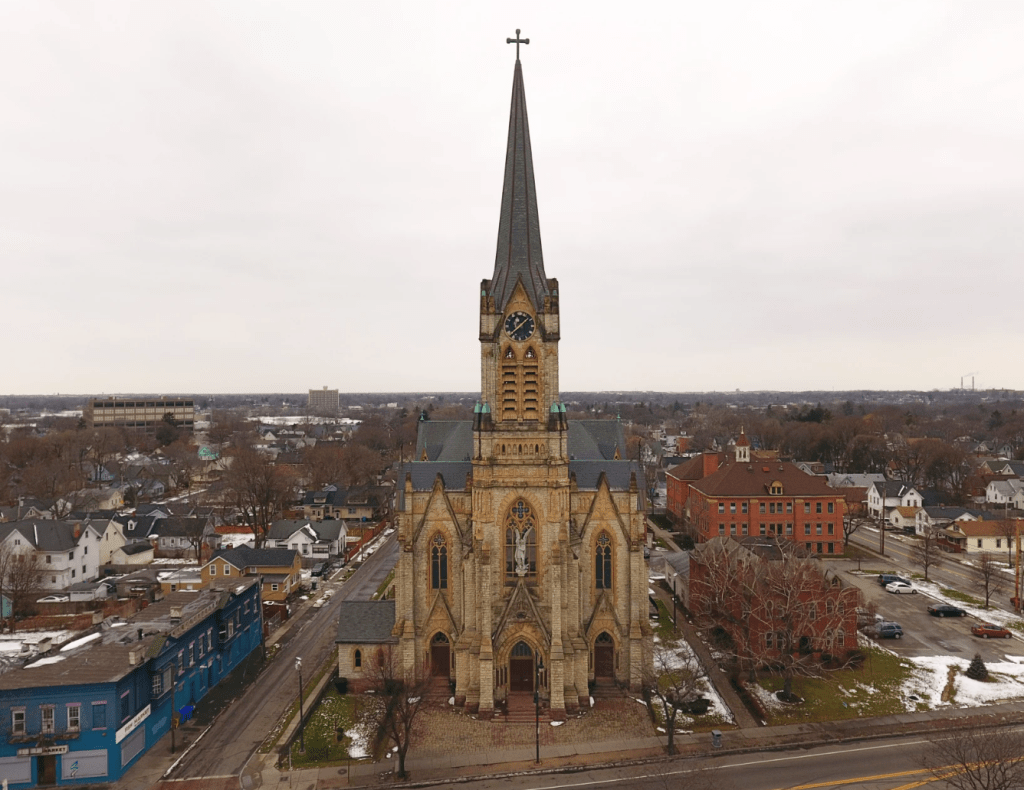

“In 1860, work began on the new church. It was a three story brick building which was to house a rectory, church and school. On June 8, 1861, the church was dedicated and placed under the patronage of St. Boniface, a saint from the same part of Germany, as many of the new parish’s parishioners.” History of St. Boniface Church

This political complexity was mirrored in the religious landscape. The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 had established the principle of cuius regio, eius religio (whose realm, his religion), but the reality in the borderlands was far more nuanced. In the village of Eiterfeld, for example, parish records from the 1760s show a surprising degree of religious mixing, with Catholic, Lutheran, and even a few Calvinist families living side by side. Our ancestors were devout Catholics.

The psychological experience of living in borderlands can be profound and complex. Carl Jung’s concept of the “shadow” is particularly relevant, as borderlanders often grapple with conflicting identities and cultural norms, integrating or rejecting aspects of multiple cultures. This internal struggle can lead to what Gestalt psychologists might describe as an “unfinished situation,” where individuals feel perpetually caught between different worlds, unable to fully resolve their sense of belonging. Modern psychological research has shed light on the unique stressors faced by those living in border regions.

Oil on canvas, artist unknown

As psychologist Ricardo Ainslie notes, “The borderland dweller lives with a constant tension between here and there, between insider and outsider status. This liminality can be a source of both creativity and anxiety.” Indeed, studies have shown higher rates of anxiety and depression among border populations, often linked to the uncertainty and instability inherent in these regions. However, this “in-between” status can also foster resilience and adaptability. As anthropologist Gloria Anzaldúa eloquently put it, “To survive the Borderlands you must live sin fronteras, be a crossroads.”

The Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) brought the strategic importance of this borderland region into sharp focus. As armies marched back and forth across the landscape, local communities found themselves caught in the crossfire. The Kister and Abel families, residing in the villages of Reckrod, Soisdorf, and Eiterfeld, experienced the war’s devastation firsthand. These communities lay directly in the path of French armies, suffering frequent occupation and pillaging. A poignant entry in the diary of a farmer from near Bad Kissingen reads, “Today the Prussians came, tomorrow it may be the Austrians. We feed them all, for what choice do we have? But our barns grow empty, and winter approaches.” The war’s impact on these families was profound, with records indicating significant population decline and economic hardship in their villages. For instance, Soisdorf’s population dropped from 305 in 1742 to 246 by 1760, showing the war’s toll on civilian life.

Yet, amidst the turmoil, there were also opportunities. The presence of multiple armies created a booming market for provisions and supplies. Some enterprising individuals, like the Bad Kissingen innkeeper Hans Müller, managed to prosper. His account books from the period show a steady increase in profits, accompanied by a note that reads, “In times of war, a well-placed inn is worth its weight in gold.”

The experiences of the Trost and Frank families exemplify the long-lasting impact of borderland dynamics on generational economic strategies. The Trosts, believed to have been merchants and innkeepers in the German borderlands, later continued this entrepreneurial tradition upon settling in Upstate New York in the mid-19th century. Similarly, the Franks, who had been grocers and tavern owners, arrived in the United States with substantial financial resources, likely accumulated through similar wartime commerce as described in Hans Müller’s account books.

again, similar to Portland and the Willamette River divide

– & both river names are from the Indigenous languages

These families’ economic success in their new homeland can be traced back to the adaptive strategies developed in the fluid borderland environment of 18th century Germany. Their ability to navigate complex political and economic landscapes, honed in the crucible of constant change and conflict, proved invaluable in the dynamic frontier economy of 19th century America. This transatlantic transfer of skills and capital illustrates how the borderland experience shaped not only individual lives but also long-term family trajectories, contributing to the economic fabric of immigrant communities in the United States.

The borderland status of the region also fostered a unique intellectual climate. The University of Fulda, founded in 1734, became a meeting point for scholars from different territories. Its library catalog from 1770 reveals an impressive collection of works from across Europe, suggesting a level of intellectual cosmopolitanism that belied the region’s provincial status. This commitment to education was deeply ingrained in the culture of these borderland communities, a value that immigrants like the Trost and Frank families carried with them to their new homes in the United States.

Upon settling in Upstate New York, these families prioritized the establishment of churches and schools, reflecting the importance they placed on education and spiritual life. Census records from their new communities confirm this dedication, showing high literacy rates among both the immigrants and their American-born children. This emphasis on education and intellectual pursuits demonstrates how the cultural values shaped by borderland experiences in Germany continued to influence these families’ priorities and community-building efforts in their adopted homeland.

It would be a mistake to romanticize life in these borderlands. For many, the reality was one of hardship and uncertainty. Tax records from the period show frequent complaints about double taxation, as individuals with property straddling borders found themselves subject to the demands of multiple sovereigns.

The fluid nature of borders in this region could lead to personal tragedies, as illustrated by church records from Eiterfeld. These documents recount the story of a young couple whose marriage was delayed for years because they were born on opposite sides of a territorial boundary, necessitating complex negotiations between ecclesiastical authorities. This example sheds light on the potential challenges faced by individuals like Theodore Frank and Elisabetha Homan. Their elusive records might be explained by a similar situation, where the complexities of cross-border relationships and bureaucratic entanglements made documentation difficult or inconsistent.

As the 18th century progressed, efforts to rationalize and solidify borders intensified. The rise of cameralism, an economic doctrine emphasizing efficient state administration, led to more rigorous border controls and customs regulations. A report from a Hessian customs official in 1785 boasts, “Our new system of border patrols has reduced smuggling by half. The state’s coffers swell, while the petty profiteers gnash their teeth.”

For genealogists and family historians, understanding these border dynamics is crucial. The fluid nature of borders and jurisdictions in this period often resulted in inconsistent record-keeping practices. A family might appear in the parish records of one territory one year, only to be recorded in a neighboring jurisdiction the next. This complexity underscores the importance of consulting multiple sources and understanding the historical context when tracing family histories in these border regions.

As we reflect on the experiences of these 18th century “border people,” we are reminded of the enduring human capacity to adapt to and thrive in complex political and cultural landscapes. Their stories offer valuable insights into the nature of identity, community, and statecraft in a world where borders were constantly negotiated and redefined. In our increasingly interconnected world, these historical experiences continue to resonate, offering lessons on resilience, adaptability, and the enduring importance of local communities in the face of larger political forces.

EXTRA: Recall above it was mention to note the proximity of the village of Schlitz near Eiterfeld and the ancestors? Check this out … this writer lives in the Willamette Valley where the hops for this German style beer comes from now. One if never far from their history, are they?

References

Ainslie, Ricardo C. “The plasticity of culture and psychodynamic and psychosocial processes in Latino immigrant families.” Crossings and Dwellings: Restored Jesuits, Women Religious, American Experience, 1814-2014, edited by Kyle B. Roberts and Stephen R. Schloesser, Brill, 2013.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Aunt Lute Books, 1987.

Conrad and Křížová. “Borders in Early Modern History (ca. 1500–1800).” Mental Mapping: Developments in the Early Modern Period, 2023.

Crecelius, Wilhelm. Oberhessisches Wörterbuch. G. Jonghaus, 1897.

Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von. Briefe. Edited by Karl Robert Mandelkow, vol. 1, Christian Wegner Verlag, 1962.

Hessisches Staatsarchiv Marburg. Bestand 40a Rechnungen II, Nr. 1456, “Beschwerden über Doppelbesteuerung,” 1745-1780.

—. Bestand 55a Zollsachen, Nr. 237, “Bericht über neue Grenzkontrollen,” 1785.

—. Bestand 90a Fulda, Nr. 1023, “Bericht über die politische Lage des Fürstbistums,” 1756.

Jung, Carl Gustav. “Psychology and Religion.” The Collected Works of C.G. Jung, vol. 11, Princeton University Press, 1938.

Lewin, Kurt. A Dynamic Theory of Personality. McGraw-Hill, 1935.

Stadtarchiv Bad Kissingen. Bestand Gasthof “Zum Goldenen Stern,” Rechnungsbücher 1756-1764.

Stadtarchiv Fulda. Nachlass Kaufmann Johann Georg Schmitt, Tagebuch 1765-1780.

Staatsarchiv Würzburg. Nachlass Familie Eckart, Tagebuch von Hans Eckart, 1759-1763.

Universitätsbibliothek Fulda. Bibliothekskatalog 1770.

Vega, William A., et al. “Help seeking for mental health problems among Mexican Americans.” Journal of Immigrant Health, vol. 3, no. 3, 2001, pp. 133-140.

This article was researched with the assistance of PerplexityAI

NARRATIVE STRATEGIES

Want help researching your family history beyond the names on your family tree? Have you been wanting to try out AI for your genealogy research? Are you stuck in your ancestry project and can’t quite figure out where or what to explore next? Inquire in comments or through link.

I value your thoughts and opinions; please share them here.